Operating Advice

Three Paths to Going Public

INTRODUCTION

IVP is a later-stage venture capital firm with $8.7B of cumulative committed capital. We’ve invested in over 400 companies, of which 122 have gone public, including seven so far in 2021. We are experts in helping our companies transition to the public markets and recently strengthened our team with the addition of Ajay Vashee, who was most recently the CFO at Dropbox (NASDAQ: DBX), where he led the company’s IPO in 2018. There has never been a better time to consider a public listing, given the strong demand for technology public offerings, and there are now several paths that companies can take to access the public markets: a traditional IPO, direct listing, and SPAC combination. We recently hosted a panel moderated by Ajay that featured the CFOs of three IVP portfolio companies — Coinbase (NASDAQ: COIN), CrowdStrike (NASDAQ: CRWD), and Hims & Hers (NYSE: HIMS). Each CFO took a different path to enter the public markets, and we were fortunate to hear their first-hand accounts. During that event, we discussed navigating the public markets in the midst of a pandemic, managing readiness efforts, and evaluating the trade-offs between the three paths to going public. Our event was hosted on Hopin and if you missed it, you can watch a recording here.

We wrote this blog post to help demystify why companies go public, how companies go public, and what to consider when deciding on a path to the public markets. In it, we’ve synthesized the key learnings from our event, and also highlighted the tradeoffs between each of the three paths to going public. If you are a CEO, COO, CFO, finance executive, or just someone who is interested in how companies transition to the public markets, this content is for you. Let’s dive in!

WHAT DOES IT MEAN TO “GO PUBLIC”?

Why do companies want to go public?

Going public is an important milestone for founders, employees, and investors. When a private company “goes public,” it begins trading on a public stock exchange (e.g. Nasdaq, NYSE) and the public is able to freely buy and sell shares of the company. There are many reasons why a company may want to go public, but the primary reasons are as follows:

- Access to capital

- Liquidity for investors and employees

- Currency for making acquisitions

- Marketing / branding event

Going public allows your company to tap into significantly larger pools of capital that can help finance continued growth, international expansion, and acquisitions. Being publicly traded makes your company’s stock liquid and gives founders, employees, and investors an opportunity to sell their shares to the public. Being a publicly traded company also makes it easier to use equity to finance acquisitions because the underlying shares are fully liquid and can be sold for cash at any time. It can also make your company’s equity compensation feel more “real” to prospective employees and can make it easier to attract top talent.

“We were able to raise a convert about a month after going public, which then satisfied our need for capital at a very low cost of capital. Once you are public, you just have so many more structures and so many more options for capital.” – Alesia Haas (CFO, COIN)

Going public is also an important marketing event that can help draw attention to your company and serves as a stamp of approval from public market investors. The process of going public is arduous, and typically only well-run businesses with strong controls and business fundamentals are able to make the leap. Public companies are viewed as less risky than private companies, which can make it easier to do business with larger corporations. Going public is a powerful opportunity to tell your story to the world and elevate your company’s profile.

“A big reason [to go public] was around brand awareness. Back in the day there were a lot of big competitors who had done well in cybersecurity but we thought that we had a different approach to cybersecurity, one that we felt would be much more effective. So, branding was huge. We were not known in all four parts of the globe so we were trying to bring out that awareness.” – Burt Podbere (CFO, CRWD)

What are the drawbacks of going public?

Going public creates extensive reporting requirements where companies must disclose financial results, executive compensation, and material updates to the general public. This means that your competition and customers will see your financials regularly, making it much harder to operate in stealth. Public companies file 10-K/10-Q’s every quarter and host quarterly earnings calls where discerning research analysts and investors dissect the business in detail. Public companies also face more intense scrutiny from the media, regulators, and investors, and must take extra precautions in regard to compliance and managing MNPI (material non-public information).

We’d also note that most employees at technology startups are accustomed to seeing their company’s valuation increase in each subsequent financing round. As a public company, your stock is freely traded, which can make the inevitable ups and downs of your company’s stock price a major distraction for employees. Being publicly traded can also make companies more short-term oriented because of the focus on “hitting the quarter.” That said, we strongly believe that the benefits of going public far outweigh the drawbacks. Going public is an important milestone in any company’s journey and is a forcing function that levels up a company’s management team, internal processes, and financial controls.

Public Readiness

Preparing for a public listing can take 12 months or longer. Prior to going public, many internal processes will need to be buttoned up and your company will need a deep leadership team across all key functions. You will need to predictably forecast revenues and expenses, and also have several years of audited financial statements ready to share with the SEC to file your S-1. If you qualify as an “emerging growth company” (i.e. a company with <$1B of revenue), you will only need two years of audited financials, though many companies still choose to include three years of audited financials. Finding great advisors and consultants that can help with technical accounting, SOX compliance, tax, and other financial matters is a great way for companies to get additional support as they prepare to go public.

“The org structure I designed included a Head of FP&A, Head of Accounting, and Head of Wall Street and Strategic Finance, so that I had all three bases covered.” – Burt Podbere (CFO, CRWD)

Within 90 days of an IPO, the majority of board members must be independent, and the audit, compensation, and nominating/governance committees must all be established, also with a majority of independent directors. Board diversity is also a major consideration for companies as they prepare to go public. If your company is headquartered in California, there are laws in place that require public boards to have at least one board member from an underrepresented community by 2021, and two or three by the end of 2022, depending on the size of the board. We expect the push for increased board diversity to continue, and believe that it is a positive development for the entire ecosystem.

Public companies don’t achieve internal readiness overnight, and it takes years of hard work to be public market ready. The best companies “behave” like public companies well in advance of a public listing, so developing good hygiene early on pays off. Prior to going public, it’s helpful to run mock earnings calls with investors on your cap table and continue to refine your forecasting muscle. The late-stage and crossover investors on your cap table can be uniquely helpful in this process. As your company gets closer to going public, your finance team should closely monitor how accurately they can forecast the upcoming quarter and fiscal year, and fine tune their forecasting methodologies accordingly.

“At Dropbox, I stepped into the CFO role about a year before we got on file with the SEC to go public. For me, my initial priority was hiring a strong and experienced team around me. I hired a Chief Accounting Officer, VP FP&A, and VP Corporate Finance and Strategy; each had worked through the IPO process multiple times. We also kicked off an ERP transition from NetSuite onto Oracle Fusion. We spent a lot of time refining our forecasting muscle by running mock earnings calls with crossover investors on our cap table.” – Ajay Vashee (Former CFO, DBX)

Life as a Public Company

Life as a public company is very different from life as a private company. One of the biggest changes is that the flow of information throughout the company suddenly becomes more restricted in order to prevent uncontrolled disclosure of material non-public information. If you are a CEO that freely shares board decks with the entire company or hosts transparent weekly all-hands meetings, those typically need to be pulled back or reworked after you are public. It’s also common to see a lot of early employees leave to start their own companies or join earlier stage companies as their equity becomes fully vested. This is to be expected but can be a drag on morale for existing employees.

“We had a culture of a lot of transparency and sharing metrics, and we really had to pull back our access to data and educate the employees on what MNPI is and why it’s harmful. That has been a big cultural change for us regarding who has access to data and what people can talk about.” – Alesia Haas (CFO, COIN)

To meet the expectations of public market investors, public companies also need to get into a cadence of “beat and raise” – performing better than investor expectations in a given quarter, and raising guidance beyond investor expectations for future quarters. This means that your finance team needs to be able to accurately forecast revenues and expenses, and have a strong grasp on the different levers of the business.

Moreover, investor relations typically becomes a much bigger time commitment as a public company. As a private company, the CFO is typically responsible for updating a small handful of VCs every few months. As a public company, the CFO must spend significant time with existing investors and potential new investors, and manage the sell-side research analyst community. For a public company CFO, having the right team in place that can provide leverage to enable you to effectively manage your responsibilities is critical.

“I’d say the biggest change definitely from a time and responsibility standpoint has been on the IR side: going from updating a handful of VCs once every three months to talking to buy-side folks, existing investors, potential investors and keeping up with the sell-side.” – Spencer Lee (CFO, HIMS)

THE THREE PATHS TO GOING PUBLIC

Companies can now access the public markets through a traditional IPO, direct listing, or a SPAC. Before deciding which path to follow, it’s important for the management team to discuss goals and expectations. Are you optimizing for speed, control, capital, or dilution? How much control are you willing to give up? There are many tradeoffs between each of the three paths, so it’s important for the management team and board to align on key objectives.

“My best advice is that you really need to align on your first principles. Why are you going public? What are the goals? Make sure that everyone is very clear on what those are before you make the decision on the structure of how you go public.” – Alesia Haas (CFO, COIN)

The traditional IPO has historically been the most common path to the public markets, but there’s been a significant increase in the number of SPACs in 2020 and into Q1’21. Direct listing activity has also picked up, and we expect many more companies to consider this path in the future. See below for data on new public market listings in recent years.

The main differences between the three paths to going public center around the ability to raise capital, the overall cost of capital, and other considerations such as lock-up mechanics, investor selection, fees, ability to issue forward-looking guidance, and transaction speed. At IVP, we often get asked about the trade-offs between each of the three paths, so we created the diagram below to highlight key considerations and illustrative timelines.

TRADITIONAL IPO

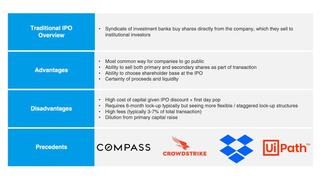

What is a Traditional IPO?

In a traditional IPO, your company raises capital by selling shares directly to a syndicate of investment banks, who then sell the shares to institutional investors and list them on a public stock exchange (e.g. Nasdaq, NYSE). A company that takes the traditional IPO route will work with an investment bank like Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, or JP Morgan, to help navigate regulatory requirements, draft regulatory filings, price the shares, and sell the shares to investors in their network. The first step of the traditional IPO process is to select an investment banking syndicate and determine who the bookrunners and co-managers will be. Investment banks will pitch the company in a “bake-off” where they make the case for why their bank is most qualified to take the company public based on past transaction experience, industry expertise, and strength of relationship. The “bookrunners” are typically listed on the top row of the front page of the IPO prospectus and the “lead left” bookrunner acts as the lead financial advisor on the deal. There is always significant jostling by the banks on who is selected to be “lead left,” as the designation commands a higher share of fees and prestige.

The traditional IPO process is a rigorous one, where your syndicate of banks helps draft your S-1, introduces your company to the research analyst community, takes your company on a “roadshow” to meet prospective investors, and eventually “builds the book” to determine IPO allocations. The first step of the traditional IPO process is to draft an S-1, which is a prospectus that includes everything an investor needs to know about your company (e.g. company overview, financials, ownership, market size, executive compensation, risk factors). Once a first draft is complete, your lawyers will send it to the SEC to review and provide comments. This is followed by a “quiet period” where the SEC reviews the S-1, and management and investors are significantly limited in what they can discuss about the company publicly. During this review period, the banks often pre-market the deal to institutional investors in their network in a process known as “testing the waters” and begin to triangulate on an initial price range based on investor feedback, which is reflected in an amended S-1. The investment banks then take your company on a roadshow where the CEO and CFO pitch institutional investors and begin taking orders. After the roadshow is complete and all orders are taken, the bankers will meet with the management team to “price” the IPO, which is reflected in the final S-1. Once the IPO is priced, the banks begin to determine allocations to investors and attempt to construct the optimal long term shareholder base for your company. After your company goes public through a traditional IPO, only the new shares issued as part of the deal are immediately tradable, and shares held by existing shareholders are typically “locked up” for 180 days to reduce volatility in the stock.

What are the advantages of the Traditional IPO Process?

The biggest advantage of the traditional IPO is the level of control that companies have on the overall listing process. The traditional IPO gives issuers complete control over their shareholder base selection, IPO pricing, and trading restrictions post IPO. The traditional IPO also comes with out-of-the-box equity research coverage from the investment banking syndicate, which is crucial for newly-minted public companies. Traditional IPO underwriters will also help market your company to institutional investors and provide connectivity to the public market investment community. In a direct listing, your company is responsible for managing and cultivating these relationships, which requires additional dedicated in-house resources.

Criticisms of the Traditional IPO Process

Recently, the traditional IPO has come under scrutiny for how expensive it can be from a dilution and transaction fee perspective. The investment banks that manage the IPO hand-select the investors that are allowed to participate in the transaction and typically recommend pricing the deal with an “IPO discount,” a lower price than the stock is expected to trade at in the public markets. The IPO discount is meant to entice investors to put an order in early to “build the book” and generate demand for the offering. The investors that an investment bank selects are typically mutual funds or hedge funds that have long standing relationships with the bank. Recent technology IPOs have been criticized as being underpriced given their large first day “pops” (i.e. when a stock trades up significantly from the IPO price). First day pops have historically been celebrated by the media as a sign of a successful IPO, but this view has been contested in recent years. When a company sells 10M shares at $30 per share in a traditional IPO and there is a first day pop of 30%, this means that there was $90M of cash left on the table that could have been on the company’s balance sheet (10M * 30% * $30 per share). Traditional IPOs can also be very expensive given the fees charged by the banks that are netted out of the IPO proceeds. The syndicate of investment banks that work on a transaction will typically charge a fee of 3-7% of the total offering depending on the size of the transaction. The fees are split amongst the syndicate, with the lion’s share allocated to the bookrunners.

To be clear, we believe that investment banks can add tremendous value during the IPO process, but we also believe that it’s important for CEOs and CFOs to understand the trade-offs and limitations of each of the three paths. The typical pricing approach and high transaction fees associated with a traditional IPO can make the route an expensive way to access the public markets, which is why other options have become increasingly popular in recent years.

DIRECT LISTING

What is a Direct Listing?

In a direct listing, your company’s shareholders (founders, investors, and employees) sell shares directly to the public, versus to a group of investors hand-selected by an investment bank in a traditional IPO. From a preparation and public readiness perspective, a direct listing is very similar to a traditional IPO. Your company still works with an investment bank during the direct listing process, but the investment bank acts as an advisor rather than an underwriter. The transaction fees in a direct listing are typically lower than in a traditional IPO or SPAC, but we’ve never seen a company pick the direct listing path for the lower transaction fees alone. Picking the right investment bank for the transaction is crucial given the nuances of a direct listing. The advisor you pick will need to help educate investors on the company and also conduct price discovery with existing shareholders to unlock supply. While it may seem like buyers and sellers should be able to align on a market price themselves through an auction, there is actually a very complex process that occurs behind the scenes to make this happen.

The direct listing process is very similar to a traditional IPO in many ways. Your company files an S-1, the SEC reviews it, and your company will be subject to a “quiet period” until the registration is public, a period where no additional marketing or communications can be made regarding the offering. Once the S-1 is publicly filed, your company will host an investor day and meet with larger institutional investors to build demand for the offering. Your company technically becomes a public company once the S-1 flips public (before any shares are actually traded) and will be able to issue forward looking guidance immediately, which allows buyers to develop a perspective on valuation.

“You can easily switch from a direct listing to an IPO, but there’s challenges of going from an IPO to direct listing. So when in doubt, file your initial S-1 as a direct listing because you always have the option to change it.” – Alesia Haas (CFO, COIN)

Ahead of trading, the company and its financial advisors will hone in on a “reference price” for the offering, a price recommended by the investment banks to help buyers and sellers determine their bids and asks, but not deterministic of where the stock may actually open. There isn’t a standard yet for determining this price, but it’s generally informed by recent secondary sales in the private markets. Setting the reference price is an important part of the direct listing process as it influences the supply of stock available for the opening trade. The price needs to be high enough to encourage existing shareholders to commit their shares, but not so high that it discourages potential buyers. On the first day of trading, buyers and sellers of the stock will begin issuing buy and sell orders until the market hones in on an “opening price,” the price at which the first shares are bought and sold. Once supply and demand are sufficiently matched, the stock begins trading on an exchange. The benefit of this approach is that the company’s stock opens at the true market price versus an artificially discounted price commonly seen in a traditional IPO. Another benefit of the direct listing is that there isn’t a lock-up required like there is with a traditional IPO. This means that existing shareholders are able to freely trade their shares immediately without having to wait 180 days, as is typically the case in a traditional IPO.

Direct Listing + Raising Primary Capital

Direct listings have historically only allowed existing shareholders to sell shares as part of the transaction, and companies were unable to sell primary shares alongside secondary shares. Both the NYSE and Nasdaq have recently introduced rules that will allow companies to raise primary capital as part of a direct listing. As of June 2021, no company has taken advantage of these new rules, and the requirements and process to do so remains unclear. Once this precedent is set, and companies can raise primary capital and also take advantage of the more favorable pricing and lower transaction fees of a direct listing, we believe that this will be a very popular path to the public markets in the future.

Stock Administration

One of the trickiest parts of a direct listing is managing the stock administration process. In a direct listing, all existing shareholders have the ability to sell their shares, including thousands of employees and all of your investors. The direct listing is a very new way to access the public markets, so it’s also typically the first time that your investors and employees are going through the process. And there are typically no lock-ups in a direct listing, which means everyone’s shares are free to trade on day one. The process of getting those shares broker ready and able to transact at the time of the opening trade is a complicated and time consuming process.

“There are archaic rules to de-legend shares to move them to executing brokers and that process is 10x more work [in a direct listing] versus an IPO so you need to put in a lot of effort and get the right advisors. There are amazing stockholder counsels that can guide companies through this but that takes time and a lot of employee education and white glove service to get right.” – Alesia Haas (CFO, COIN)

Are Direct Listings for Everyone?

Direct listings are a relatively new way to access the public markets and there have only been a handful of companies that have executed direct listings so far. Many of these companies are household names (e.g. Coinbase, Spotify, Slack, Roblox) and even the less well known ones (e.g. Asana, Palantir, ZipRecruiter, Squarespace) are still fairly high profile. One of the key components to a successful direct listing is volume, given the need for adequate supply and demand at the opening trade, which is why only higher profile companies have taken this route. That being said, direct listings are becoming increasingly popular, and we expect more and more companies to pursue them.

SPAC

What is a SPAC?

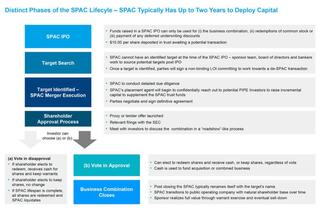

SPAC stands for “Special Purpose Acquisition Corporation” and is a way for private companies to go public through a reverse merger. Reverse mergers / SPACs have been around for decades but have recently increased in popularity following Social Capital’s Hedosophia Holdings SPAC in 2017. Since then, SPAC volume has exploded, with 245 IPO transactions and $86B raised in 2020 alone. Q1’21 was a record quarter for SPAC issuances, but there has been a significant decline in SPACs in Q2’21 given increased scrutiny from the SEC and macro volatility in the public markets.

How does a SPAC work?

In a SPAC, a “SPAC Sponsor” creates a shell company and takes it public through a traditional IPO. A SPAC is often called a blank check company because it is a shell company with no operations. The money raised in the IPO is put into a blind trust that generates interest and is what justifies the market cap of the SPAC. The funds put into the trust can only be used to complete an acquisition or return money to the investors, should the SPAC be terminated. When a SPAC goes public through an IPO, it issues “SPAC units” that are usually priced at $10 per unit. Each unit translates into a common share and additional full or partial warrants to entice investors to buy at the SPAC IPO. A warrant is a financial security that gives the owner the right to purchase a certain number of shares of common stock in the future at a certain price. After the IPO, the SPAC units can be separated into common stock and warrants which can be traded freely in the market. If the SPAC is terminated, the underlying warrants have no value, but the common shares retain their value and can be redeemed. The SPAC sponsor will typically receive ~20% ownership of the outstanding shares post IPO to compensate them for their work in identifying an acquisition target, which is also called the “Sponsor Promote.” The SPAC sponsor will sometimes also receive additional warrants based on performance milestones.

Once the SPAC is public, the SPAC sponsor will source potential companies for the SPAC to acquire. SPACs typically have two years to complete an acquisition before funds are disbursed back to shareholders. Once a target is identified, the SPAC will raise a PIPE (Private Investment in Public Equity) to help fund the transaction and begin the de-SPAC process. The PIPE serves two purposes: 1) it allows the SPAC to provide more capital to the target company, and 2) SPAC sponsors use the PIPE to help validate an acquisition price (i.e. large hedge funds or mutual funds will typically participate in the PIPE). The SPAC target will need to be public market ready with audited financial statements, achievable financial projections, and a compelling public market story. Once the merger is complete and the combined entity is publicly traded, the combined entity will is subject to the same rules and regulations as a company that goes down the traditional IPO or direct listing path.

De-SPAC

The de-SPAC process occurs after the execution of the definitive agreement and is similar to what happens in a public company merger. Because the SPAC is a publicly traded company, there needs to be a formal shareholder vote to approve the merger. The SPAC will hold shareholder meetings, fill out proxy statements, and receive SEC approval before the transaction is finalized. The SPAC shareholders will vote to approve the transaction, and if the transaction is approved, the target company will become a part of the publicly traded holding company and thus become publicly listed themselves. The target company will need to file a form 8-K and satisfy the SEC’s requirements regarding reporting, audited financial statements, and tax compliance. The combined entity must then comply with all the reporting and regulatory requirements of publicly traded companies. If the acquisition is rejected, the SPAC investors can either elect to redeem their shares or keep their shares until the SPAC finds another acquisition target or is terminated.

What are the advantages of a SPAC?

One of the commonly cited advantages of a SPAC is the speed at which companies can go public. In theory, the SPAC process can take 4-6 months to complete, compared to 10-12+ months for a traditional IPO or direct listing. In practice, a SPAC can take just as long or even longer than a traditional IPO or direct listing, depending on how long it takes to strike a deal with the right SPAC sponsor, finalize a PIPE, and manage the SEC review process. That being said, because the SPAC is already a publicly traded company that has done the legwork of an IPO, the SEC documentation for a SPAC merger is significantly simpler than a traditional IPO. Another benefit of a SPAC is price certainty for the target company once a final merger agreement is reached, which is an attractive feature that is unique to SPACs. We’d note that there is no price certainty unless the PIPE investors also agree to the price. We’ve observed situations where the SPAC sponsor offers a high headline price but has to walk it back after engaging with PIPE investors.

“We wanted to raise primary capital so it was just a decision between a traditional IPO and the SPAC. As we evaluated the two choices, I think the three things that stood out that we really valued with the SPAC were certainty, timing, and flexibility.” – Spencer Lee (CFO, HIMS)

SEC Scrutiny

SPACs have recently faced increased scrutiny from the SEC, which has caused new SPAC issuances to contract in Q2’21. The SEC has raised questions regarding the accounting treatment of SPAC warrants, which has caused audit firms to rethink the consents they include in SPAC registration statements. SPAC warrants have historically been accounted for as “equity” on company balance sheets, but the SEC has recently suggested that these warrants should be classified as “liabilities”. SPAC targets in pending de-SPAC transactions and the combined companies that have already de-SPACed will need to review their accounting treatment of warrants and may need to potentially restate their historical financials, which has caused a slowdown in SPAC activity. In addition to the potential change in accounting treatment for warrants, the SEC is also considering limiting the ability of SPACs to issue long term outlooks in their merger proxies. The increased SEC scrutiny and poor trading performance of companies post de-SPAC (relative to the broader market) have resulted in a slowdown in new SPAC issuances.

CONCLUSION

We hope this blog post was helpful in understanding the different options that companies have when considering a public listing. It was meant to provide a high-level overview of the three paths to going public, and we plan on releasing more content on how companies should approach public readiness in the future. A special thanks to Alesia Haas, Burt Podbere, Spencer Lee, and Jeff Thomas for participating in our panel, as well as Daniel Tay of Morgan Stanley for reviewing previous drafts of our blog post.

Michael Miao and Ajay Vashee are Investors at IVP, a later-stage venture capital firm.

*The information provided in this blog does not, and is not intended to, constitute as legal advice; instead, all information, content, and materials available on this blog are for general informational purposes only. *